December 8, 2016

On November 18, Republican Vice President-elect Mike Pence attended a performance of Hamilton, Lin-Manuel Miranda’s multicultural hip-hop retelling of the life of the titular founding father. Miranda had used songs from the musical to campaign for Democrat Hillary Clinton, and was publically against the Republican platform, particularly its plank on immigration. In response to Pence’s attendance, he collaborated with director Thomas Kail, producer Jeffrey Seller, and the current to cast to craft a statement to be read after the curtain call. As soon as the bows were complete, actor Brandon Victor Dixon (who portrayed Vice President Aaron Burr) asked Pence to wait a moment before leaving the theatre. As the audience began to boo, he made the following remarks:

There’s nothing to boo. We’re all here sharing a story of love. We have a message for you sir, we hope that you will hear us out. […] Vice president-elect Pence, we welcome you and we truly thank you for joining us here at Hamilton: An American Musical. We really do. We, sir, are the diverse Americans who are alarmed and anxious that your new administration will not protect us: our planet, our children, our parents, or defend us and uphold our inalienable rights. But we truly hope this show has inspired you to uphold our American values and to work on behalf of all of us. All of us. Thank you truly for seeing this show, this wonderful American story told by a diverse group of men, women of different colors, creeds, and orientations.

<iframe allowfullscreen=”” frameborder=”0″ height=”315″ src=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/aWlwrUFiuUw” width=”560″></iframe>

Pence was not bothered by the statement; he listened from the lobby, and took the audience boos in the spirit of the first amendment, saying they were “what freedom sounds like.” President-elect Donald Trump was another matter. The following morning, Trump took to Twitter to excoriate the cast of Hamilton:

The Theater must always be a safe and special place.The cast of Hamilton was very rude last night to a very good man, Mike Pence. Apologize!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) November 19, 2016

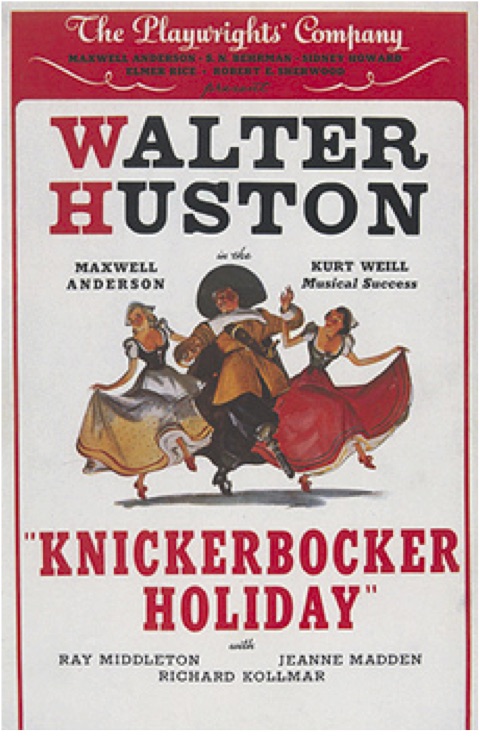

But Trump’s description of theatre as a “safe” space where politicians can take a break from the world of governance does not hold up to historical scrutiny (Craft). Playwrights, composers, actors, and other theatre professionals have used Broadway to criticize politicians and the political process throughout the twentieth century. While to my knowledge a cast has never directly addressed a politician from the stage, there have been cases where elected officials went out of their way to see or support shows that were openly critical of their positions. One case stands out as particularly relevant to the Hamilton kerfuffle: Kurt Weill and Maxwell Anderson’s Knickerbocker Holiday, which took on President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the New Deal in 1938. The show is remembered only for the immortal “September Song,” largely because its politics don’t resonate with today’s audiences, but like Hamilton, Knickerbocker Holiday is an American origin story. It takes place in Dutch New Amsterdam in the 17th century, with a story that concerns the arrival of the tyrannical Governor Pieter Stuyvesant. The townsfolk realize that being American means fighting for liberty and freedom, and so they reject the governor’s reign of terror (Fig. 1).

On October 15, 1938, FDR attended Anderson and Weill’s musical, where he was treated to a viciously satirical vision of his presidency. Anderson, who probably would be called a libertarian today, believed that Roosevelt’s New Deal was a criminal governmental power grab that paved the way for fascism. In the “Preface to the Politics of Knickerbocker Holiday,” he wrote

The members of a government are not only in business, but in a business which is in continual danger of lapsing into pure gangsterism, pure terrorism and plundering, buttering over at the top by a hypocritical pretense at patriotic unselfishness. The continent of Europe has been captured by such governments within the last few years, and our own government is rapidly assuming economic and social responsibility which take us in the same direction (Anderson vi).

In order to make his point, Anderson turned the historical Governor Stuyvesant into a stand-in for the President (Fig 2). The idea was particularly pointed given that Roosevelt was one of Stuyvesant’s successors; he’d been governor of New York between 1929 and 1932. Anderson painted Stuyvesant as a greedy, power-mad tyrant disguised as a populist, who hid all of his unsavory agenda in the fine print of his policies. When Stuyvesant first arrives in New York, he delivers a stump speech that lays out his plans:

STUYVESANT: From this date forth the council has no function except the voting of those wise and just laws which you and I find that we need! From this date forth all taxes are abolished! [a tremendous cheer goes up.] Except for those at present in effect and a very few others which you and I may find necessary for the accomplishment of desired reforms. [The CROWD looks a little worried] (Anderson 41).

To add insult to injury, one of those corrupt councilmen is named Roosevelt (based on the president’s direct ancestor). Before Stuyvesant’s arrival, the character Roosevelt leads the council in a “Dutch”-dialect song describing their governmental philosophy:

ROOSEVELT: Ven you first come to session

For making of der laws

You liff on der salary only

But you don’t make no impression

And you don’t get no applause

And der guilders dey look so lonely

So you maybe ask a question of a fellow standing by

And he nefer gives an answer, and he nefer makes reply

But he slips a little silver and he looks you in the eye

And he says, “Hush, hush,” to you (Anderson 11).

Weill actually admired Roosevelt and was somewhat uncomfortable with Anderson’s politics (Juchem 81), but nevertheless supported the message of the drama with his music. He gives the “government” characters of Stuyvesant and the council old-fashioned European idioms. Roosevelt’s song “Hush Hush” is an old-fashioned polka with a bouncy “oom-pah” accompaniment. For Stuyvesant, he composed “All Hail the Political Honeymoon,” a militaristic march that the souvenir program referred to as “Prussian,” linking the would-be tyrant (and therefore Roosevelt) with Hitler. Stuyvesant even sings of “an age of strength through joy,” evoking the well-known Nazi slogan “Kraft durch Freude” (Anderson 44). For the younger generation, particularly the hero Brom Broeck (who proclaims himself the “first American”), Weill composed typical Broadway-style numbers to emphasize their inherent “American-ness.” The breezy soft-shoe “There’s Nowhere to Go But Up” and the forceful foxtrot “How Can You Tell an American?” communicate the essential optimism and individualism that formed Anderson’s vision of the nation’s best characteristics.

Despite the fact that the musical accused Roosevelt of being corrupt, incompetent, and proto-fascist, the President apparently enjoyed the performance. The newspapers wrote that he “laughed heartily” (Hinton 280), although he may have been trying to prove that he was a good sport. By 1938, he may also have developed a relatively high tolerance for Broadway making fun of him. The Pulitzer-prize winning Of Thee I Sing by George and Ira Gershwin mocked his difficulties with the Supreme Court in 1932, and Rodgers and Hart’s I’d Rather Be Right starred the legendary George M. Cohan as Roosevelt himself in 1937. Roosevelt seemed to take it all in stride.

One interesting aspect of the Knickerbocker Holiday story is that Weill was not a citizen when the show premiered. He had arrived in the United States as a Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany only three years prior and applied for citizenship in 1937, but the process was not complete until 1943. This may be why the issue of who is and who isn’t an American infuses the story. Like in Hamilton, Weill’s America is made up of a contentious group of immigrants and native-born citizens struggling to define their new nation. Also like in Hamilton, Weill and Anderson framed their historical story in ways that resonated with contemporary audiences. During the 1920s and 1930s, stages were rife with “Dutch” acts, but they did not come from The Netherlands. Rather, they came from Germany, with “Dutch” a mispronunciation of “Deutsch.” “German/Dutch” was often elided with Yiddish, so that many of these “Dutch” acts played into the notion of what John Koegel calls “the immigrant Everyman” (189). Many of the German immigrants of the 1930s were like Weill: Jews who fled Nazi Germany, but who had trouble finding a place to settle. Many nations feared that the flood of refugees would not be able to assimilate, or worse, concealed German spies in their numbers (Graber 264–66). Knickerbocker Holiday opened only two months after the Évian Conference, a summit where world leaders attempted (unsuccessfully) to figure out how to cope with the tide of German-Jewish refugees. Amidst this cultural climate, Knickerbocker Holiday tells the story of how immigrants can become loyal American citizens.

Perhaps Knickerbocker Holiday was Weill’s way of reminding Roosevelt (already fairly pro-immigration) and the rest of the nation that the first Americans were immigrants—that “immigrant” and “American” were synonymous rather than mutually exclusive. While the older generation of immigrants resist assimilation, the younger generation sings in the familiar pop music styles of the time, demonstrating that they could indeed assimilate into—and maybe even improve—American culture. If nothing else, Knickerbocker Holiday proves that immigrants do indeed get the job done.

– Naomi Graber